Our goal is to manufacture DNA nanostructures with desired size by using DNA origami technology. Shape-complementary interfaces on DNA origami enables us to stack DNA origami blocks to form a large-scale polymeric object. However, the number of stacking is still difficult to be controlled.

Here we show that through designing the configuration and arrangement on protrusions and recessions of DNA origami surface, the number of stacking origami blocks can be precisely controlled.

We designed an origami which has an ability to transform its shape triggered by an input of single-stranded DNA. When we add the input, initial shape (closed state) is changed into another shape with different width/height(open state).Owing to the shape- complementary interfaces, only the combination of closed state and open state can stack with each other. Based on the principle of least common multiple, the stacking procedure continues until the width/height becomes identical. Moreover, by adjusting the width/height ratio between closed state and open state, it is possible to realize DNA nanostructures with designated size made of one kind of blocks.

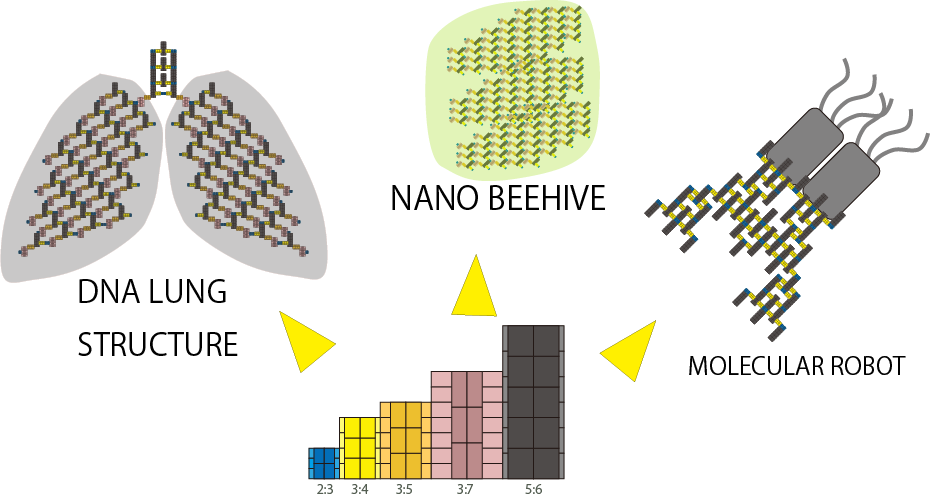

We anticipate that our design will be a starting point to make micro-scale DNA nanostructures. For example, the cytoskeleton for artificial cell, the body of molecular robots and the base of nano chemical factory could be manufactured. Furthermore, combining our method with DNA computing could provide a brand-new possibility for molecular robotics.

Project

Background and Motivation

The entire biological world can be regarded as a huge hierarchical system composed of homogeneous and heterogeneous layers. For example, proteins, which are made up of only 20 kinds of amino acids, can form complicated structures with diverse functions by folding and assembling themselves in a controllable way. And they are one of the basic components of organelles and cells which are at a totally different scale. Inspired by this self-organizing hierarchy, we considered manufacturing DNA nano structures with designated size.

Purpose

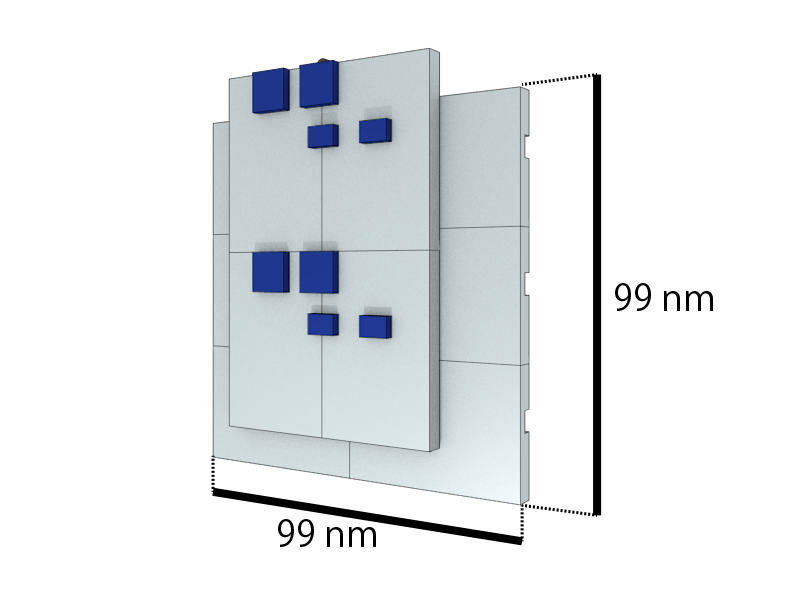

DNA origami technology enables us to make various nanoscale structures [1]. However, the maximum size of DNA origami is limited to 100 nm due to the length of the scaffold. Although DNA origami could stack together on the basis of the shape-complementary interfaces, the number of stacking cannot be controlled [2]. In order to create large structures by stacking DNA origami blocks, we need many kinds of origami with different connectors. The purpose of our project is to create structures with designated size by stacking only one kind of DNA origami blocks in a controllable way.

Idea

To achieve the purpose, we proposed a new method to control the number of stacking origami blocks. In this method, a shape-complementary interface with protrusions and recessions on both sides is designed. By adjusting the length/width ratio of the origami blocks, the stacking procedure could stop at a specified height in accordance with the principle of least common multiple. Furthermore, the origami blocks have abilities to transform from closed state to open state, providing the possibility to use only one kind of block to build origami architecture like a tower, while avoiding the improper stackings.

Procedure

Our approach consists of the following 3 steps.Step1: Design

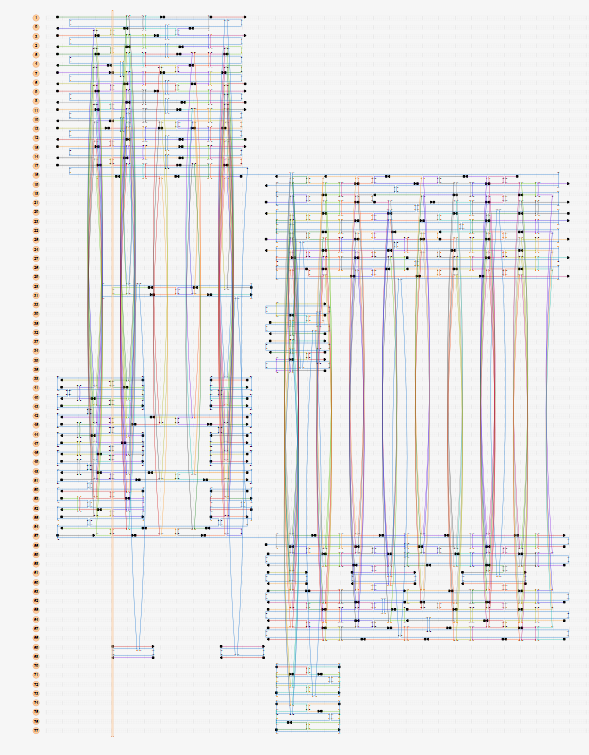

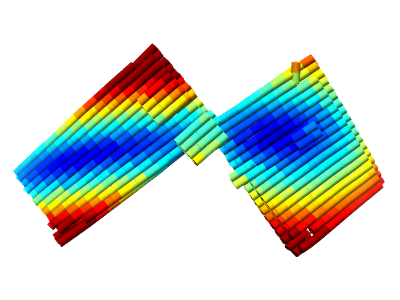

- The shape-complementary interface of DNA origami blocks is designed by caDNAno2. The thermodynamic stability of the DNA origami is simulated by CanDo. Its molecular dynamic property is simulated by oxDNA.

- The opening/closing mechanism to control the activation of the origami block is designed by Sequence Design, and NUPACK is to confirm the desired strand displacement reaction.

Step2: Simulation

- A mathematical model for stacking reactions by reaction kinetics is formalized.

- The behavior of the model is predicted by Scilab.

Step3: Experiment

- Origami preparation: Make DNA origami with strands of opening/closing mechanism

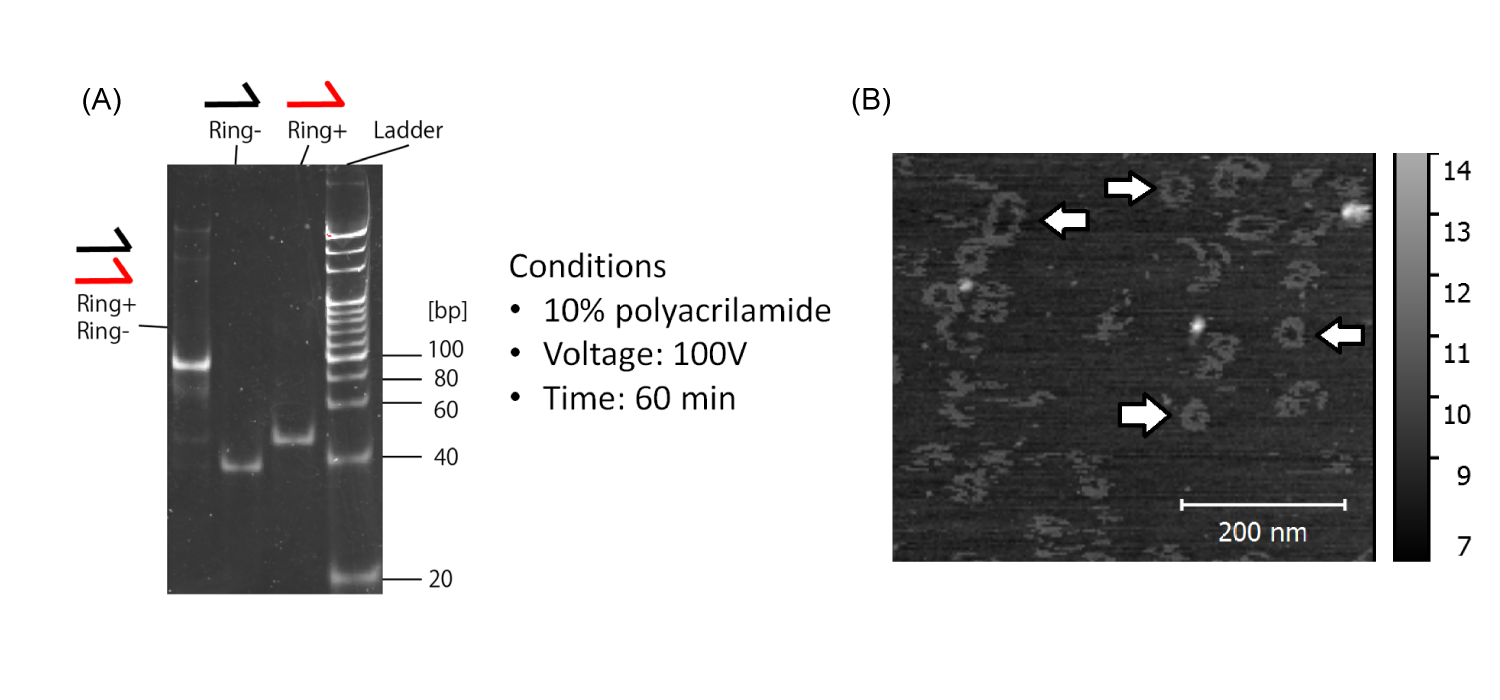

- Poly-Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Verify the behavior of opening/closing mechanism.

- Observation by Atomic Force Microscope: Verify the shape of DNA origami blocks, the transformation from open state to closed state, and the stacking procedure.

Future

Our mechanism enables us to make micro-scale DNA nano structures. For example, the cytoskeleton for artificial cell, the body of molecular robots, molecular computers, and the base of nano chemical factory could be manufactured.

Design

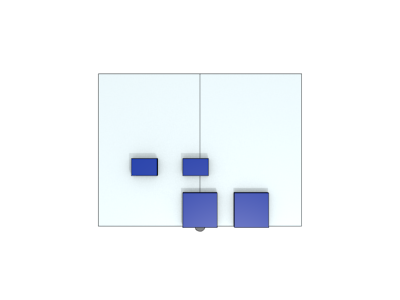

We build a tower by using only one kind of DNA origami block (Fig 2-1).

The block is composed of two components that are connected by a hinge. The hinge provides the block two different states (open and close). (Fig.2-2A~2-2C).

pX:

dX:

currentFrame:

src:

drag:

displayMode:

blockOpened:

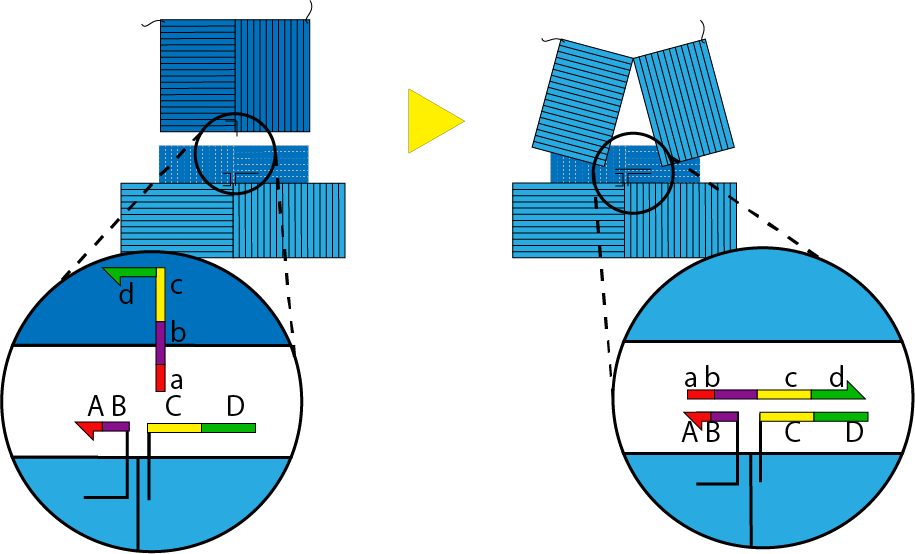

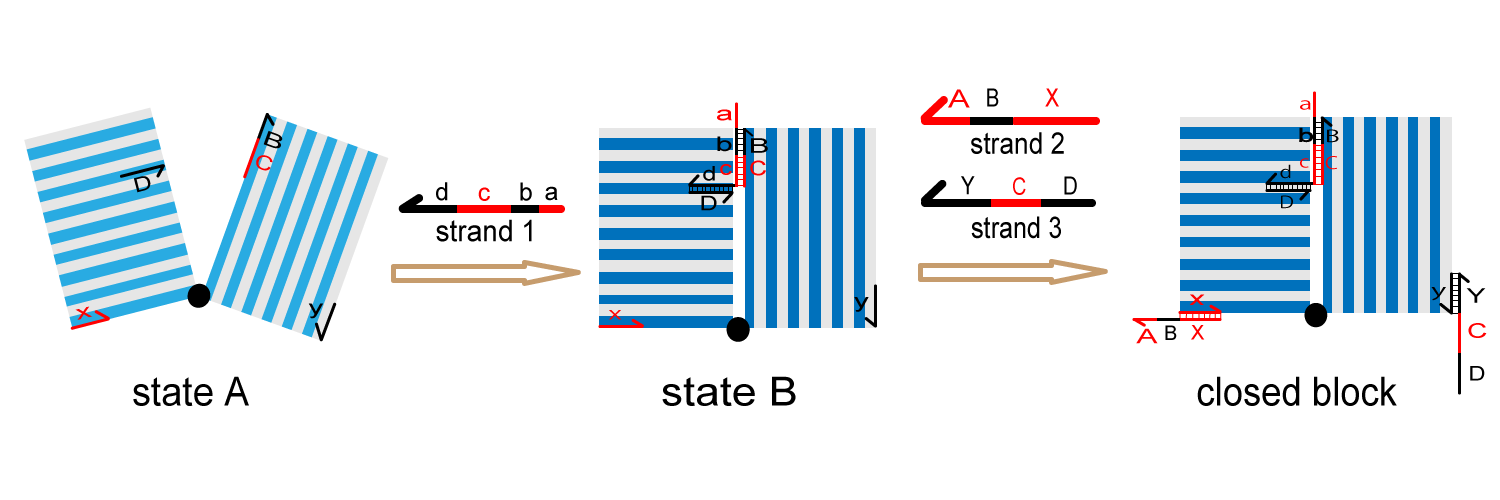

There is a report that DNA structure with protrusions and recessions can stack together [2]. Employing this mechanism, we designed blocks that have protrusions on obverse surface (Surface A) and recessions on reverse surface (Surface B). Moreover, nucleobase stacking interactions engage at the double-helical interfaces of the shape-complementary protrusions and recessions when the two domains are brought into contact, but only upon correct fit of helices and given correct helical orientation of the interfacial nucleobase pairs. Therefore, only Surface A of closed state and Surface B of open state have the ability to stack with each other (Fig.2-3).We designed the origami block by caDNAno2.[3]

We also designed an opening/closing mechanism to realize the transformation from closed state to open state. In Fig. 2-4, we graft some single-stranded DNAs to the origami blocks. When we add the initial input of a single-stranded DNA, which has the complementary sequences to the ones grafted to the blocks, closed state transforms into open state due to the strand displacement reaction. Once the block becomes open state, it has the ability to activate the next closed block.

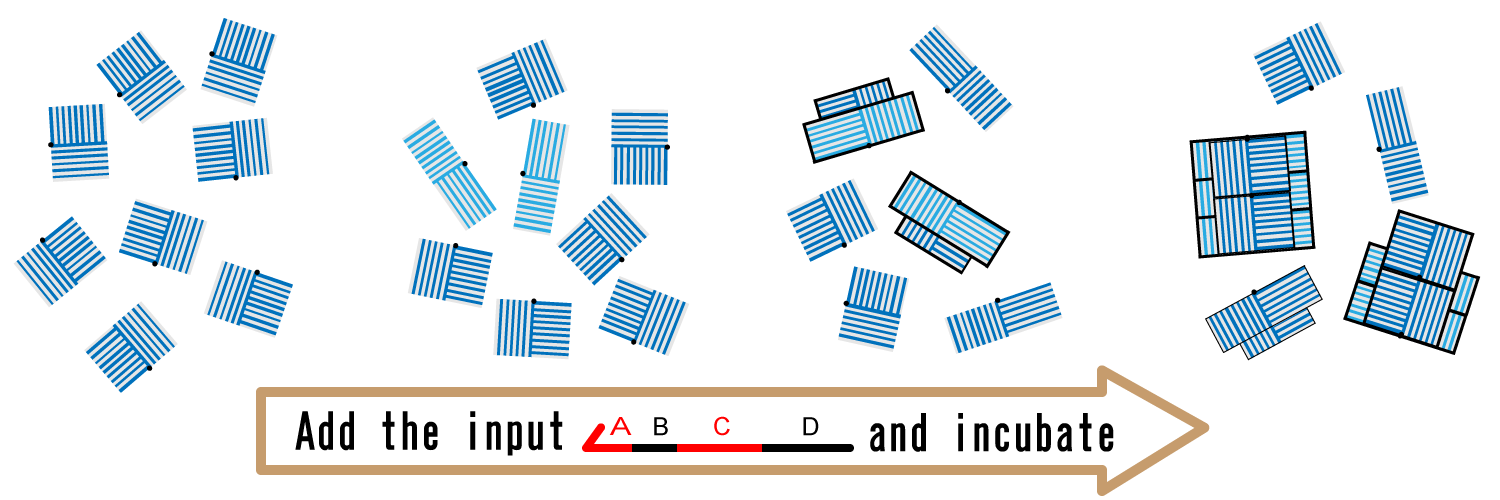

We controlled the height of the tower, namely the number of stacking blocks, according to the principle of least common multiple (Fig.2-5). For example, if we intend to build a 6-story tower, we prepare an origami block which has two pairs of protrusions on Surface A and three pairs of recessions on Surface B. Through the opening/closing mechanism mentioned above, we could realize the situation where there are two closed blocks and three open blocks and the stacking procedure would stop when all the six pairs of protrusions and recessions combined with each other. Generally, we could build polymeric blocks with any designated height by changing the length-width ratio of the monomer blocks.

Simulation

1.Dynamics

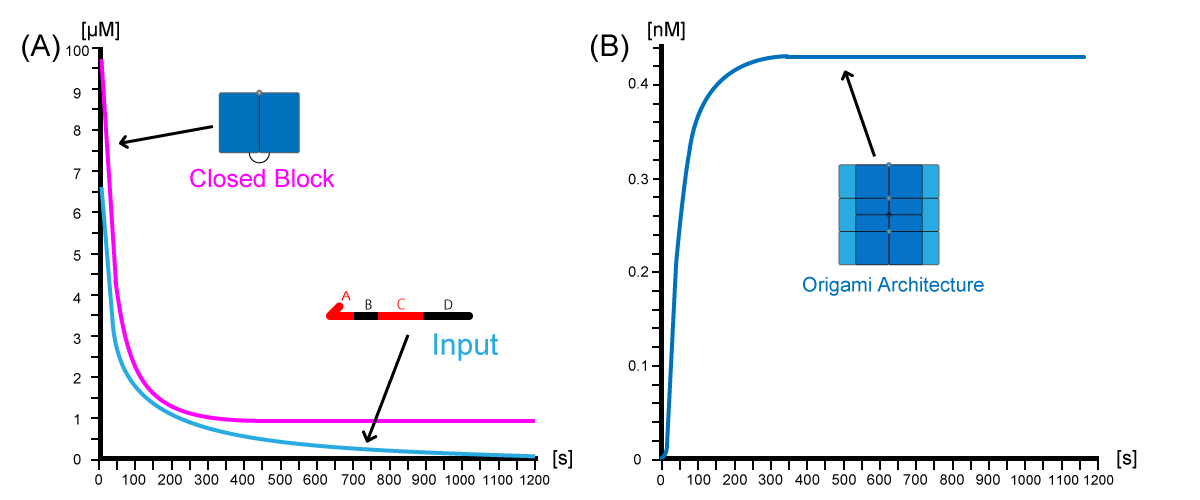

The DNA blocks are connected with each other and gradually form large scale intermediates by DNA stacking, then eventually enlarge up to the expected size. In order to confirm the process of building the architecture, we formalized a simulation model with ordinary differential equations based on chemical kinetics. By running the simulation with Scilab, we obtained the time series graphs of concentrations of stacked blocks including the intermediates. We show The list of intermediates and the source code.

When the input strand was added at 0 [s], the concentration of the input and the monomer block rapidly decreased and gradually converged to 0 [nM] and 10 [µmol/L], respectively (Fig.3-1A). This reflects the reaction that the monomer block reacted with the input strand. On the other hand, the concentration of origami architecture increased swiftly (Fig.3-1B). It finally reached about 0.44 [nM]. The concentration of architecture became the half concentration of the equilibrium state after 50 [s]. This indicates that DNA blocks were rapidly connected with each other and build up to the final expected size.

(B)Time-dependent concentration plot of origami architecture

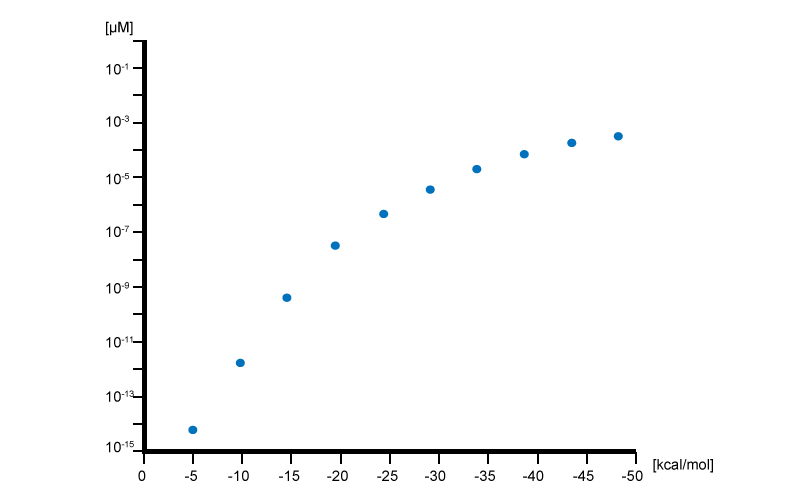

2.Gibbs free energy and the concentration

We calculated equilibrium constant and rate constant from a difference between Gibbs free energy by using the following equation.

Then we regard the free energy difference as a variable and carried out simulations for each value to understand the relation between the free energy and the yield of the architecture (Fig 3-2). Each plot corresponds to the concentrations of the architecture at 1200[s] after reaction starts under given free energy. When the free energy difference was small, the concentration of the architecture increased. Note that free energy difference is a negative value. A smaller value represents a more stable architecture. To improve the yield of origami architecture, we need to minimize the free energy difference obtained by the stacking of DNA blocks.

Experiment

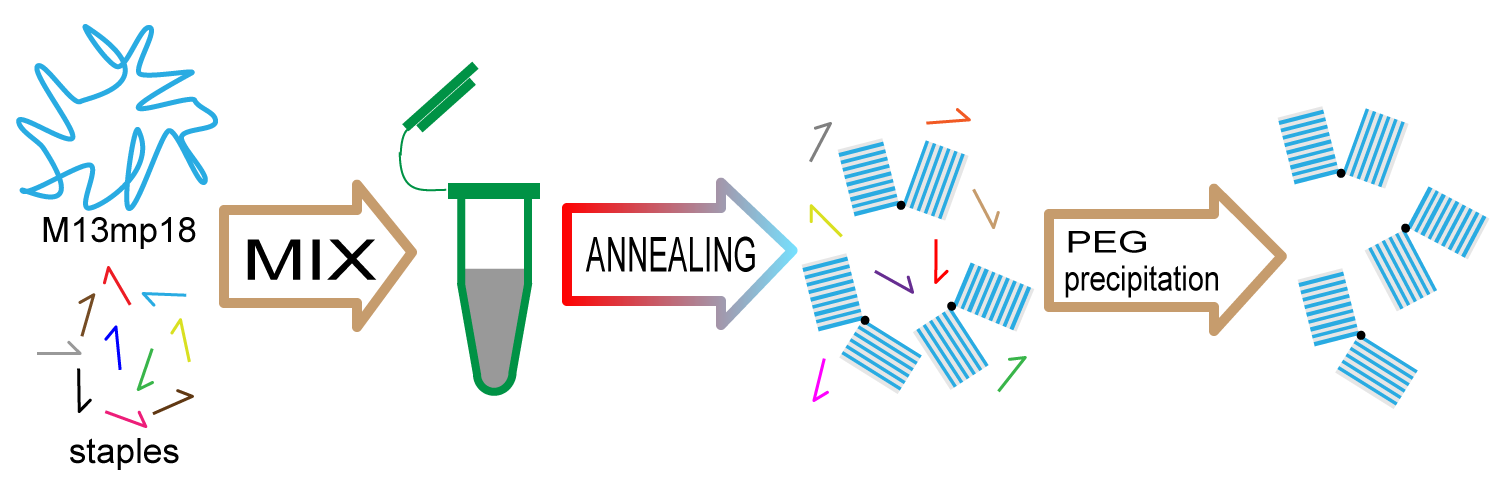

1. Preparing DNA origami

We prepare DNA origami in the following steps.

(1) Mixing M13mp18 and staples

(2) Annealing

(3) Purifying origami with PEG precipitation

2. Preparing monomer block

We prepare the monomer block in the following steps to prevent undesirable hybridization.

(1) Mix state A block and strand 1 and incubate to form closed-state block.

(2) Mix state B block, strand 2 and strand 3 to form monomer block.

3. Assembly

We add the input and incubate the solution to start the assembly of monomer blocks. To avoid all the closed blocks to be activated, it is required that concentration of the input is lower than that of closed blocks.

4. Observation

We are planning to observe and verify the functionality of origami structures by using electrophoresis, AFM, and photospectrometer.

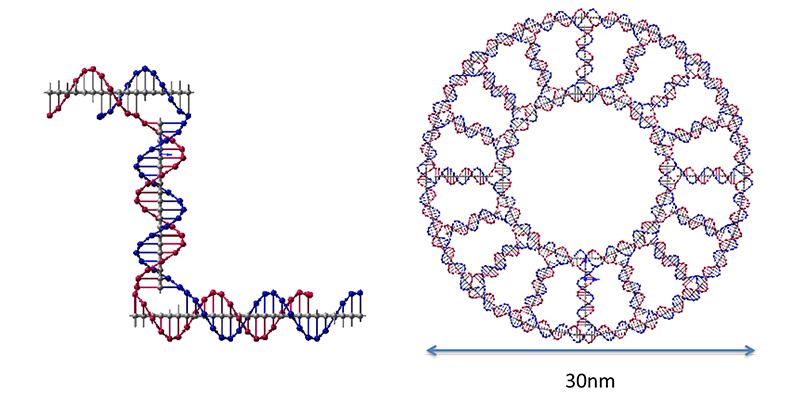

Training

In order to learn the process of sequence design and measurement of DNA nano structures, we conducted some experiments. As a case study, the DNA ring was chosen. It is made of two kinds of single-stranded DNA (Fig.4-4).

The results of electrophoresis and AFM image show that we succeeded in forming DNA rings (Fig.4-5).

(B)White arrows indicate DNA rings.

Discussion

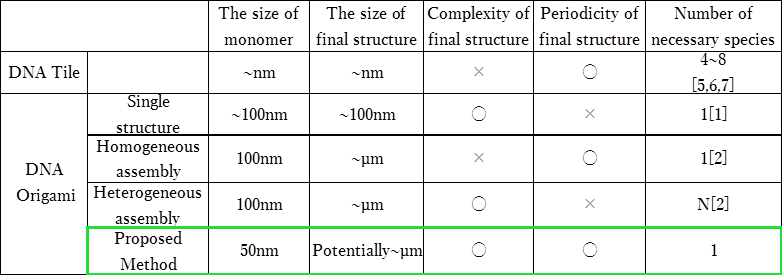

Comparison with other approaches

Compared with existing method (Table 5-1), the proposed method enables us to build large structures using homogeneous monomers. By arranging the orientation of protrusions and recessions on the surface and adjusting the length/width ratio of DNA origami blocks, we can make various structures with specified size by self-assembly.

Significance

The entire biological world can be regarded as a huge hierarchical system composed of homogeneous and heterogeneous layers [8]. The homogeneous layer is able to form the heterogeneous layer with many homogeneous components of various sizes and complexities, such as cells form various tissues and organs.

Materials&Methods

Team

Members

Freshman

Taiyo Kikkawa, Masataka Saito, Akihiko Fukuchi

Sophomore

Sho Aradachi, Yuya Onodera

Junior

Yuma Endo, Takeo Uchida, Keita Abe, Shosei Ichiseki, Satoru Akita, Shiyun Liu

Senior

Eiki Ishihara, Shunsuke Imai, Hayato Otaka, Yuto Otaki, Kenta Suzuki, Taiki Watanabe, Yoriko Hashida, Thanapop Rodjanapanyakul

Supervisor

Ryo Kageyama, Koichiro katayama, Takahiro Tomaru, Takuto Hosoya, Hiroyuki Fujino, Masahiro Endo, Satoru Yoshizawa, Koichi Kurashima, Masaru Tsuzawa, Tomoyuki Hirano, Kazuki Hirahara, Yusuke Sato, Wataru Tobita, Keitel Cervantes-Salguero, Akira Saito

Mentor

Satoshi Murata, Shin-ichiro M.Nomura, Ibuki Kawamata

Sponsors

References

[1] Rothemund, Paul WK. "Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns."Nature 440.7082 (2006): 297-302.

[2] Gerling, Thomas,Klaus F. Wagenbauer, Andrea M. Neuner, and Hendrik Dietz . "Dynamic DNA devices and assemblies formed by shape-complementary, non?base pairing 3D components." Science 347.6229 (2015): 1446-1452.

[3]S. M. Douglas et al., Rapid prototyping of 3D DNA-origami shapes with caDNAno. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 5001 (2009)

[4] Hamada, Shogo, and Murata, Satoshi. "Substrate‐Assisted Assembly of Interconnected Single‐Duplex DNA Nanostructures." Angewandte Chemie121.37 (2009): 6952-6955.

[5] Rothemund, Paul WK, Nick Papadakis, and Erik Winfree. "Algorithmic self-assembly of DNA Sierpinski triangles." PLoS biology 2.12 (2004): e424.

[6] Pistol, Constantin, and Chris Dwyer. "Scalable, low-cost, hierarchical assembly of programmable DNA nanostructures." Nanotechnology 18.12 (2007): 125305.

[7] Rothemund, Paul WK, and Erik Winfree. "The program-size complexity of self-assembled squares." Proceedings of the thirty-second annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. ACM, 2000.

[8] Murata, Satoshi, and Kurokawa Haruhisa. Self-organizing robots. Vol. 77. Springer, 2012.